Natural gas is making a comeback. Here’s what to do about it

Demand from data centers, AI and cryptocurrency is fueling the fastest growth in U.S. natural gas capacity in decades. The post Natural gas is making a comeback. Here’s what to do about it appeared first on Trellis.

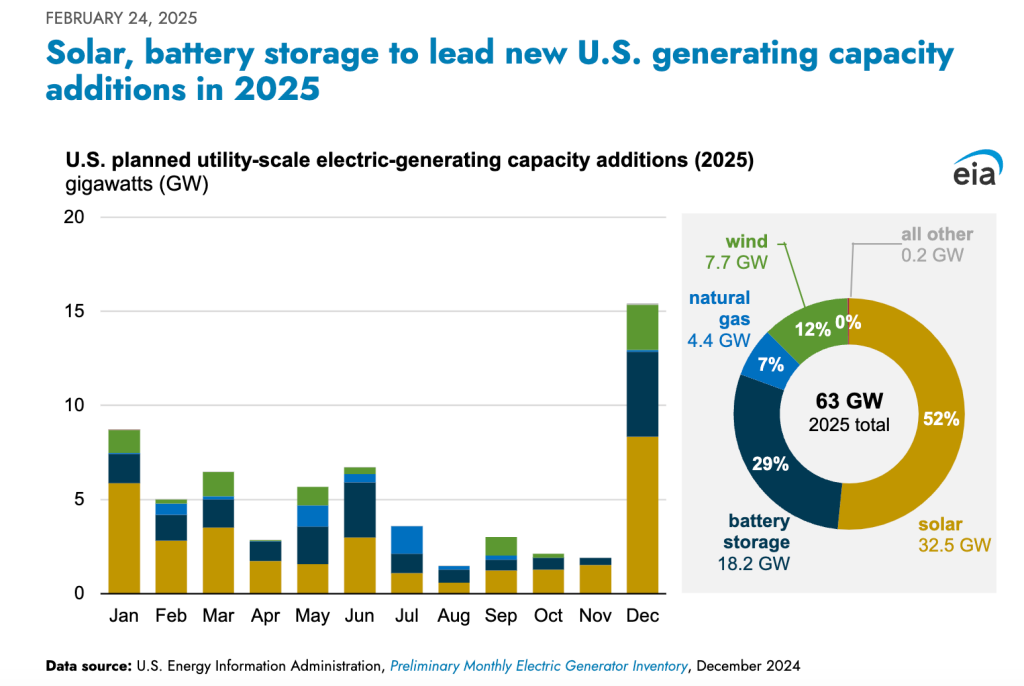

Solar installations, battery storage and wind farms accounted for the vast majority of capacity added to the U.S. electric grid in 2024.

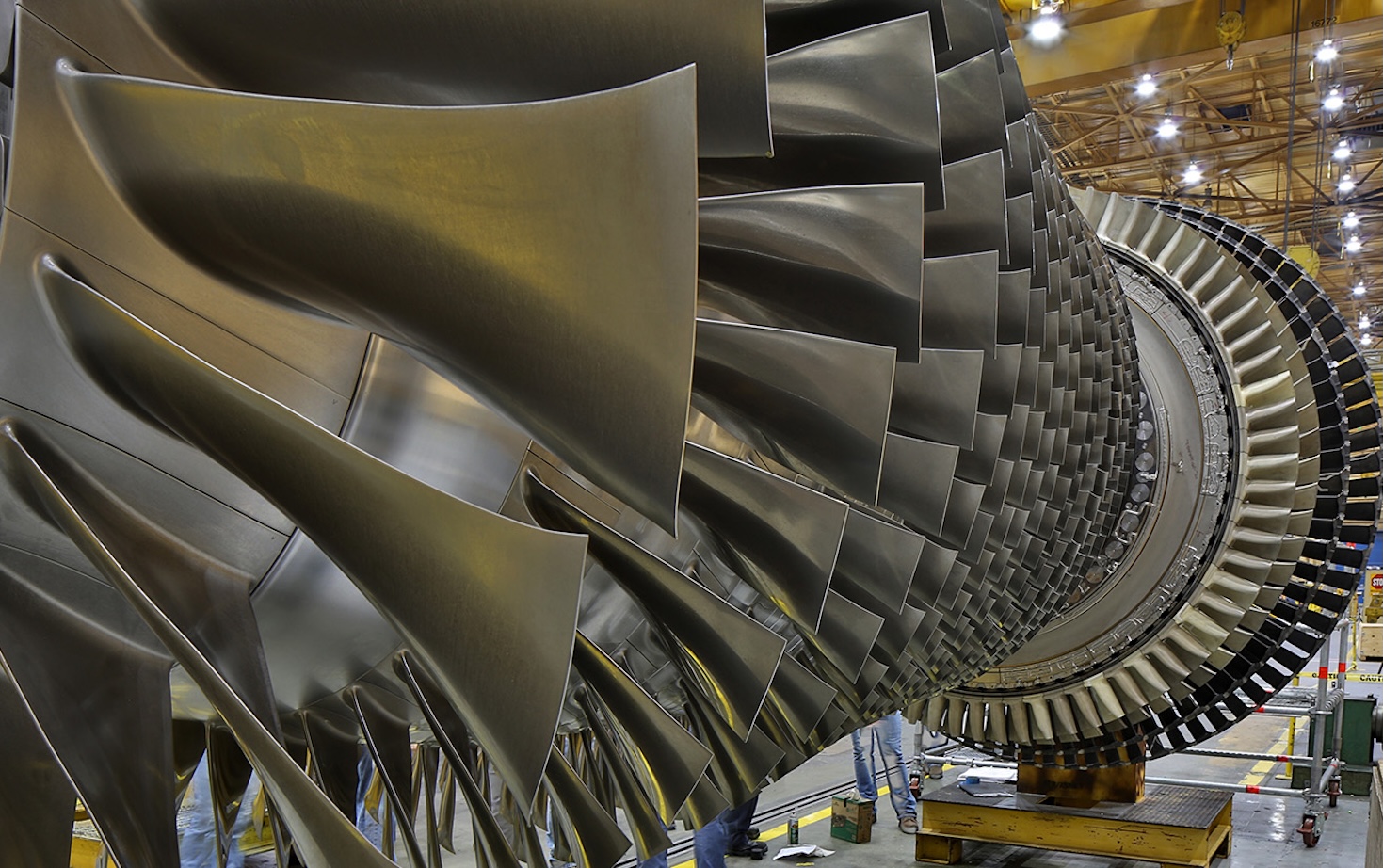

But natural gas capacity is growing the fastest it has in two decades, abetted by the voracious energy appetite of data centers operators. Those energy users include Microsoft, which is investing $3.3 billion to build a site in Wisconsin; and Meta, which is pouring $10 billion into its largest site in Louisiana.

Global electricity demand is forecast to grow by roughly 3.4 percent over the next three years. The amount used for data centers, artificial intelligence and cryptocurrency could double by 2026, according to the International Energy Agency.

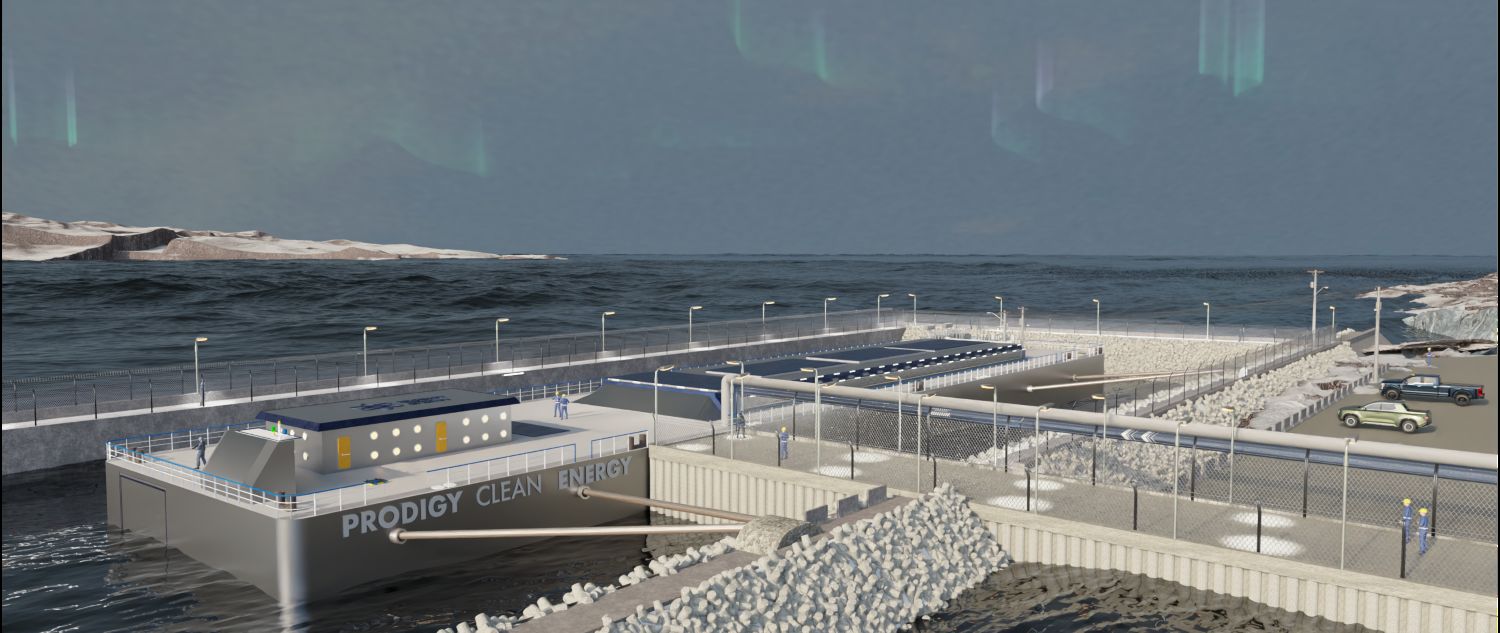

The spike in U.S. natural gas demand aligns with those projections, sparking interest in approaches that could throttle related emissions increases. One potential solution: carbon capture and storage technologies installed at power plants.

These solutions — which would suck up carbon dioxide at the source and transport it via pipe, railroad or truck to underground sequesters — could eliminate an estimated 95 percent of their carbon dioxide emissions, according to a new analysis published March 3 by carbon removal advisory firm Carbon Direct.

The approach is nascent, but the list of sites conducting engineering and cost feasibility studies is growing in states including Alabama, California, Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Texas and West Virginia. Companies working to advance this approach include legacy oil and gas infrastructure players such as Aker Solutions, Fluor, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Shell, along with new ventures including Ion Clean Energy and Svante.

“In locations where power needs are large and sustained, integrating natural gas-fired power generation with [carbon capture and storage] is an important decarbonization strategy,” the Carbon Direct analysts said. “It complements renewable and other low-carbon electricity supplies in fulfilling substantial energy demands.”

Push for ‘capture ready’ projects

Carbon capture and storage projects make sense for natural gas power plants that generate at least 100 megawatts of power on a steady basis, which emit an average of 500,000 metric tons of CO2 annually, suggests the Carbon Direct analysis.

But they wouldn’t be as effective for smaller plants or for facilities built to handle peak energy demand, said Colin McCormick, principal scientist at Carbon Direct.

Corporations with both large energy appetites and aggressive climate goals should look for “capture ready” features at natural gas plants that might serve their operations, said McCormick. These include:

- Dedicated valves and pipes to support the process

- Locations with enough space to accommodate the equipment footprint

- Transportation methods that can get the capture gases to a site for storage

It doesn’t beat renewable energy

Adding carbon capture and storage to a natural gas plant could result in a fivefold reduction in climate impacts versus a plant that doesn’t use them, according to the analysis, but solar and wind still offer better emissions reduction potential.

Natural gas with carbon capture and storage would have an impact of 80-120 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent per megawatt-hour of electricity, compared with an impact of 10-15 kilograms of CO2e per MWh with either solar or wind.

That scenario doesn’t account for potential methane emissions associated with the natural gas supply for a given project. “If poorly planned and implemented, [carbon capture and storage] could worsen those impacts,” Carbon Direct said.

Deploying carbon capture and storage at natural gas plants also costs more than other options corporations can use to reduce the climate impact of their energy purchases: an estimated $65-$100 per MWh at scale compared with current costs or $40-70 per MWh for natural gas plants without this equipment.

The calculation for that cost comparison includes tax credits for carbon capture projects under the Inflation Reduction Act, which could be repealed by the Trump administration.

“The conventional wisdom is that they would support these credits, but we don’t know yet,” McCormick said.

Other considerations:

- Upstream methane leakage: Natural gas plants outfitted to handle carbon capture will require 20-30 percent more fuel to run that process. Emissions from the supply can add 50-350 kilograms of CO2 equivalent emissions per MWh of electricity produced. The high end of that range would wipe out the benefits from carbon capture and storage.

- Local infrastructure: Pipelines will matter for delivery of the fuel. They are also the most efficient way to transport captured carbon dioxide to a place where it can be sequestered. Those costs need to be considered in any investment plan.

- Sequestration potential: Sites appropriate for sequestration are scattered throughout the Midwest, Gulf Coast, Mountain West and California. States with primacy when it comes to permitting include Louisiana, North Dakota, West Virginia and Wyoming.

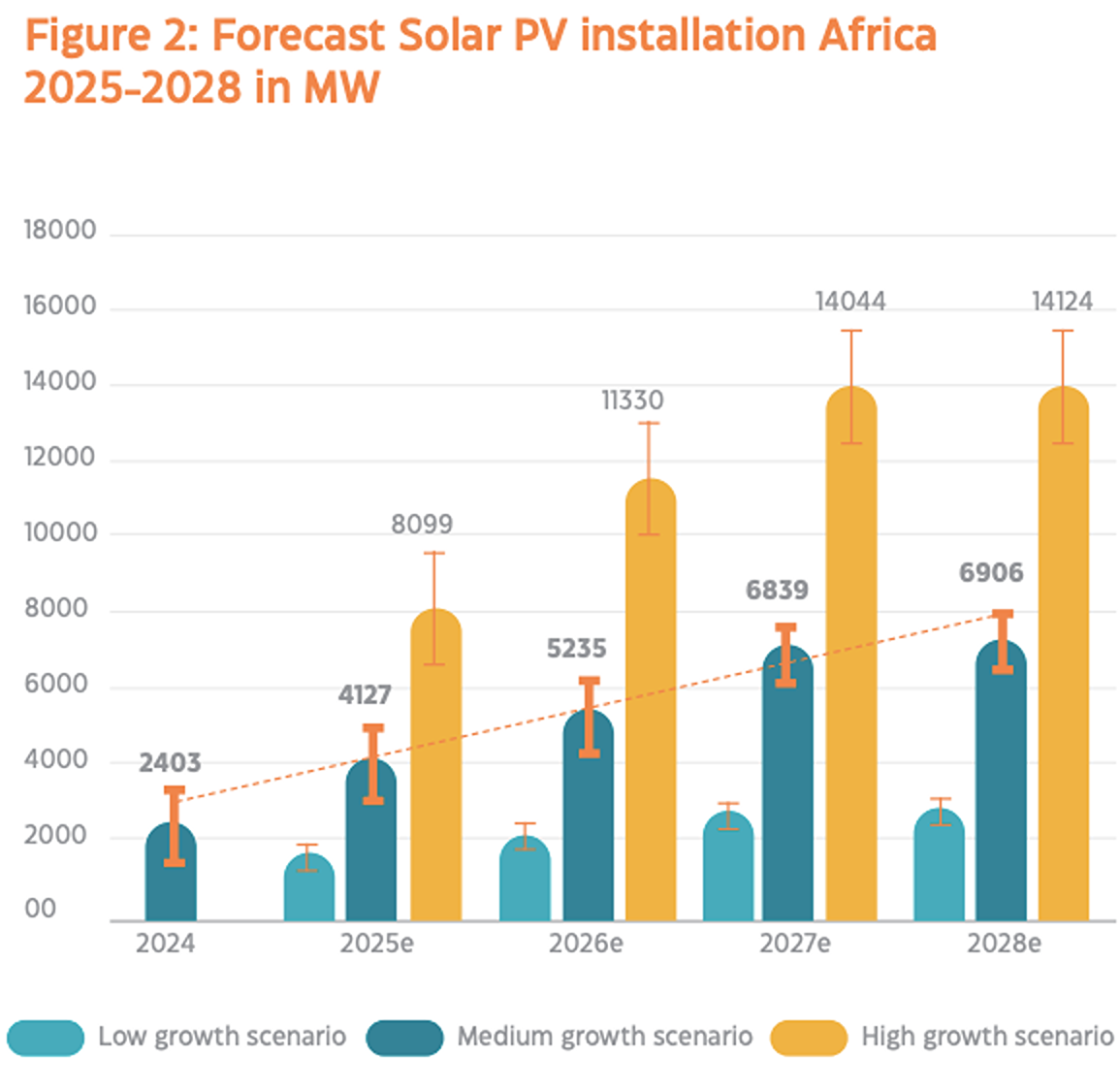

Growth scenario drives discussions

Natural gas is already the most dominant source of generation on the U.S. grid, accounting for about 43 percent of capacity as of 2024, according to government data.

At least 4.4 gigawatts of new natural gas-fired electricity could come online in Louisiana, Nebraska, North Dakota and Utah by the end of 2025, the U.S. Energy Information Administration predicts. That’s roughly the amount of power needed to keep 3.5 million U.S. homes up and running for one year.

The agency predicts total additions of 63 gigawatts for 2025. One gating factor is the long backlog for permits to interconnect new generation sources to the U.S. grid. But the Trump administration’s executive order declaring an “energy emergency” could change that dynamic for fossil fuels projects. Still, Chevron is so bullish on the opportunity that it started a new business partnership with GE Vernova, the biggest U.S. gas turbine company, to deliver up to four gigawatts of new power specifically meant to support artificial intelligence. The venture expects to begin delivering power by 2027.

The post Natural gas is making a comeback. Here’s what to do about it appeared first on Trellis.

What's Your Reaction?